| Papers & Essayes |

| On the Lost Highway: Lynch and Lacan, Cinema and Cultural Pathology |

|

"A 21st Century Noir Horror Film. "

"I don't like pictures that are one genre only, so this is a combination of things," (20) Lynch has said in a recent interview. Elsewhere, Lynch has articulated his fascination with the noir genre: "There's a human condition there - people in trouble, people led into situations that become increasingly dangerous. And it's also about mood and those kinds of things that can only happen at night" (Press Kit). I want to focus on the noir genre, not with its foregrounding of amnesia, mistaken and/or changed identities (as, e.g., in Dark Passage), of which there are obvious references in Lost Highway. I would like to concentrate on the genre's disturbed and disturbing urban environment, on the figures of mobsters and femme fatales, with respect to the Oedipal constellation that underlies the genre, and I think it is mainly in this connection that Lost Highway (and here especially the second part, Pete's story) can be regarded as a noir movie. (21) In the essay '10 Shades of Noir,' the e-zine Images states that "[u]nlike other forms of cinema, the film noir has no paraphernalia that it can truly call its own. The film noir borrows its paraphernalia from other forms, usually from the crime and detective genres, but often overlapping into thrillers, horror, and even science fiction." (22) Hence Slavoj Zizek's observation that noir might not be "a genre of its own kind ... [, but] a kind of logical operator introducing the same anamorphic distortion in every genre to which it is applied." (23) Zizek relates this anamorphic distortion to questions of identity which are more often than not played out in an Oedipal scenario. The first part of Lost Highway presents a marital scenario of uncertainty, anxiety, and unspoken suspicion. It takes place in a house which more resembles a fortress than a cosy home. From the film's beginning, we have the feeling of tension and fear: home, the family unit is the place of trouble and terror. This feeling is emphasized by Lynch's masterly employment of the soundtrack. For Lynch, "[h]alf of [a] film is picture ... the other half is sound. They've got to work together" (Press Kit). So, in Lynch's work, the soundtrack is a most important factor to enhance the mood of a scene. For example, during the dialogues between Fred and Renee there is no resonance to their voices. It is as if the works are spoken in a sound-absorbing environment, the whole spectrum of overtones, all those features that make a human voice seem alive, seems to have been cut. In its dryness, the voices of Renee and Fred almost seem to enact an absence of sound, or better - an absence of room, of the acoustics of space: it's as if they are living in a recording studio covered in acoustic tile. This soundscape underlines the similarity of this scenario with Lacan's subject being entangled in the register of the imaginary, most powerful symbolized in the child's symbiotic relationship with the Other, its mother. The incestuous two-ness is underlined by various devices. The strange lights in the Madison living-room, e.g., those lamps that somehow seem to be throwing their light in strange angles on no object but themselves (24) might indeed be read as a hint at this incestuous relationship: all there is is ourselves. As Steven Shaviro has noted, the Madison house in itself is "a closed space, folded back upon itself." (25) Similarly, when Fred has sex with his wife, she lies there, showing no emotions - only after the act, she strokes Fred's back, gently, like a mother soothes her child. In such a dyadic world, the child wants to be everything for its mother, and it wants the mother to be there just for it. (26)

Fred also feels that he is not everything to his wife. Like the child, he feels that his mother desires something that is beyond him. Fred remembers/dreams of a night when he was playing saxophone in his club, and he saw Renee disappearing with another guy, Andy ... one can see the neon EXIT sign there, and that's exactly how it is: Renee is looking for an exit/escape out of that prison-like symbiosis. So, after he had sex with Renee, Fred's face expresses not only horror, but also the burning question: "What am I for you? What am I for the Other?" So, somehow, Fred is precisely dependent on the desire of the Other, and therefore it is necessary for him that the Other, Renee, exactly remains in her position as love-giving, complete Mother, unspoiled by any lack - and it is such a lack that the mother reveals in her desire for someone else, and also the lack in the child, Fred, since he is seen as incapable of filling the lack. Thus, the imaginary scenario is an attempt of Fred's to disavow castration by all means. In the second part of the movie, Fred's story,

the Oedipal scenario is brought to the fore even stronger. Here,

now, we have Fred, the young man; Alice, the femme fatale;

and Mr. Eddy, the father-like mobster. Father, because both of his

age, and because he treats Pete with a kind of paternal attitude. In

Lacanian terminology, the father-figure is accepted by the subject

as its ideal-ego, and as such serves for the internalization of the

laws of society. However, the flip-side of this benevolent figure of

the ideal-ego is the super-ego, the father as "perverse

father," the exception at the origin of the law. The Master,

the Father, he who gives the Law is an "obscene, ferocious

figure" (Écrits 256) that "imposes a

senseless, destructive ... almost always anti-legal morality."

(28) To imagine what is at stake,

it suffices to recall Freud's notion of the Urhorde.

|

Papers | Lost Highway pages | David Lynch main page

© Mike Hartmann

mhartman@mail.uni-freiburg.de

Here, in the Madison marriage, we have a routine-version

of this symbiosis. All distance has gone, and, since desire can be

said to be exactly relying on this distance between subject and

object, desire has gone, as well. Being too near to the object of

desire causes anxiety. And indeed, there are also disturbing signs

of something that threatens to undo this imaginary wholeness. First,

there are those strange videotapes. In addition, both Fred and Renee

have an uncanny feeling of being observed; note for example Renee's

facial expression when she finds the first video, which might be

both explained by the fact that she fears that it might be one of

those porn videos she is starring in, and of which Fred does not

know anything, or by the general feeling of being observed, a

feeling that takes shape in the fact that they live close to the

"observatory." The outside literally starts to intrude the

inside, and the threat is emphasized by the deep droning sounds (in

a cinema with a good sound system, the spectators actually can

feel this threat as a uncomfortable feeling in their stomachs

... already in Eraserhead, Lynch had made use of this device,

the constant droning of a ship's engine underlying the whole movie).

Here, in the Madison marriage, we have a routine-version

of this symbiosis. All distance has gone, and, since desire can be

said to be exactly relying on this distance between subject and

object, desire has gone, as well. Being too near to the object of

desire causes anxiety. And indeed, there are also disturbing signs

of something that threatens to undo this imaginary wholeness. First,

there are those strange videotapes. In addition, both Fred and Renee

have an uncanny feeling of being observed; note for example Renee's

facial expression when she finds the first video, which might be

both explained by the fact that she fears that it might be one of

those porn videos she is starring in, and of which Fred does not

know anything, or by the general feeling of being observed, a

feeling that takes shape in the fact that they live close to the

"observatory." The outside literally starts to intrude the

inside, and the threat is emphasized by the deep droning sounds (in

a cinema with a good sound system, the spectators actually can

feel this threat as a uncomfortable feeling in their stomachs

... already in Eraserhead, Lynch had made use of this device,

the constant droning of a ship's engine underlying the whole movie).

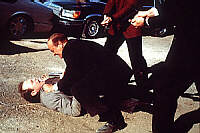

The primal father enjoyed all the women of the tribe, he was the

chieftain, the law-giver, and when his sons killed him, out of shame

the forbid themselves to "have all the women." So, at the

bottom of the law, of the incest taboo, there is the figure of the

One who had been the exception to the rule. In Lost Highway,

this becomes clear in the scene when Mr. Eddy beats and humilates a

driver for tail-gating (

The primal father enjoyed all the women of the tribe, he was the

chieftain, the law-giver, and when his sons killed him, out of shame

the forbid themselves to "have all the women." So, at the

bottom of the law, of the incest taboo, there is the figure of the

One who had been the exception to the rule. In Lost Highway,

this becomes clear in the scene when Mr. Eddy beats and humilates a

driver for tail-gating (